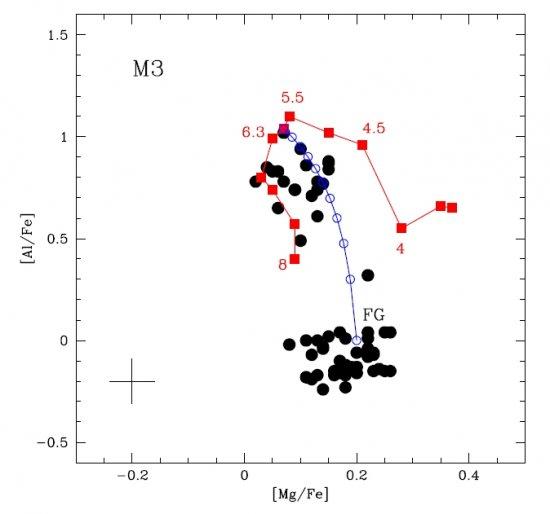

Historically, globular clusters (GCs) have been used as laboratories for studying stellar evolution, because it was thought that all the stars in a globular cluster formed at the same time and thus have the same age. However since a couple of decades ago it has been known that almost all the globular clusters contain several stellar populations. In the first generation the chemical abundances, for example those of elements such as Al and Mg, show the composition of the original interstellar (or intra-cluster) medium. In the short time (astronomically) of only 500 million years the medium is contaminated and from this medium the second generation of stars is formed. It is thought that some of the most massive stars (i.e., supermassive stars, rapidly rotating massive stars, massive interacting binaries, and massive AGB stars) in the first generation produce and destroy the heavy elements in their interiors (“nucleosynthesis”) and by rapid mass loss contaminate the interstellar medium where the second generation of stars then forms with different chemical abundances. The production of Al and the destruction of Mg in the interiors of stars is very sensitive to their temperature and overall metallicity, so they offer a good diagnostic to unveil the nature of the contaminating stars. Here we have combined the Al and Mg abundances in five GCs observed by the APOGEE survey with the nucleosynthesis models in massive AGB (asymptotic giant branch) stars (which produce these elements in their interiors, and then eject them during a phase of extremely rapid mass loss). We are able to reproduce for the first time the Al-Mg anticorrelations in these five globular clusters, spanning very different metallicities. This finding supports the idea that massive AGB stars were the key players in the pollution of the intra-cluster medium, from which additional generations of stars formed in GCs.

A graph of the results of the study, showing the relative abundances of Al and Mg relative to Fe for the evolved stars in the globular cluster M3. We can see an anticorrelation between Al and Mg for the stars in the cluster (black filled circles). The pre

Advertised on

References